Brandenburg Gate – a symbol of Berlin

It is very typical of Berlin: when the gates were officially opened on August 6, 1791, the royal building was not yet completed. The Quadriga wasn’t ready – it wasn’t set up until two years later. According to the Berliners, this makes the Brandenburg Gate even more symbolic. But that they were destined to become one of the city’s main attractions was known from the start – Kaiser Friedrich Wilhelm II had planned them to be just as luxurious and enviable.

After the Thirty Years’ War, a customs wall with eighteen entry gates was built around Berlin. These served to organize the tax revenue on goods imported into the Prussian capital. The main entrance was to be designed in a special way – a gate was to be erected, which not only performed a border function, but also served as a decoration. The construction of the gates, whose road led into the city of Brandenburg an der Havel, began in 1781. Times were peaceful, and the new gate was not originally called the Brandenburg Gate, but the Friedenstor, and the quadriga crowning it was replaced by the controlled ancient Greek goddess of peace Irene.

Friedrich Wilhelm II commissioned the Prussian architect Carl Gotthard Langhans with the work. The design was to be “conscientiously” made so that if the customs station were to be relocated the gates would remain standing and be pleasing to the eye. This is how it happened: Of the eighteen gates, only the Brandenburg gates were preserved and thus became the symbol of the capital and of all of Germany. Inspired by the Athenian Acropolis and its Propylaea, the architect used the ancient Greek style in German architecture for the first time, laying the foundation for what later became known as Berlin Classicism. It is often assumed that Berlin was nicknamed “Athens on the Spree” because of the construction of the Peace Gate, but this is not the case. In fact, the city became the cultural center of Europe by the 18th century.

The famous Berlin sculptor of that time, Johann Gottfried Schadow, created the famous quadriga crowning the gate, although in fairness it should be noted that a whole group of masters worked on it. After the work was completed, rumors circulated that the model of the goddess had been sculpted to life size and that the “model” had been Countess Wilhelmina von Lichtenau, also known as “the Prussian pompadour” and mistress of Friedrich Wilhelm II.

Also in favor of this theory is the piquant fact that the statue was originally nude, and Wilhelmina loved to pose “naked”. The commoners found this “outfit”, or rather the lack of it, inappropriate, and the goddess had to be dressed in a copper dress. Only the figure’s back remained partially exposed. However, Johann Gottfried Schadow himself claimed that the model for him was a completely different young woman, the daughter of a blacksmith from Hausvogteiplatz.

The Brandenburg Gate Quadriga has always attracted attention. In fact, it was coveted by none other than Napoleon Bonaparte, who, after his victory over Berlin in 1806, had the Quadriga dismantled into 13 boxes and taken to Paris. This action earned him the nickname “horse thief” among Berliners. Ironically, during World War II, one of the horses’ head came off exactly according to Napoleon’s disassembly plan.

On June 9, 1814, after Prussia’s victory over Napoleon, the sculptural ensemble was returned to its place – with the indecently exposed parts of the goddess appropriately covered for transport from Paris to Berlin. Since then, the gates have become a symbol of victory over France, and the goddess of peace has turned into the Roman goddess of victory, Victoria, which has been supplemented with a new element – the Prussian iron cross. In the population, the Quadriga got the nickname “Retourkutsche”, which in German means something like “answer” or “change”.

The return of the Quadriga to Berlin was entrusted to Simon Kremzer, a soldier in Blücher’s Silesian Army who had experience in transporting bulky loads. In gratitude he was granted the right to live in Berlin and became a transport entrepreneur, opening the city’s first horse-drawn bus line.

In 1871, after the victory in the Franco-Prussian War and the proclamation of the German Empire and the swearing-in of Wilhelm I as German Emperor, a huge victory parade passed through the Brandenburg Gate. The unification of the state was massively celebrated on the square opposite the gates. Almost 120 years later, on New Year’s Eve 1990, there was another celebration, this time to celebrate the reunification of Germany – a remarkable turning point in history!

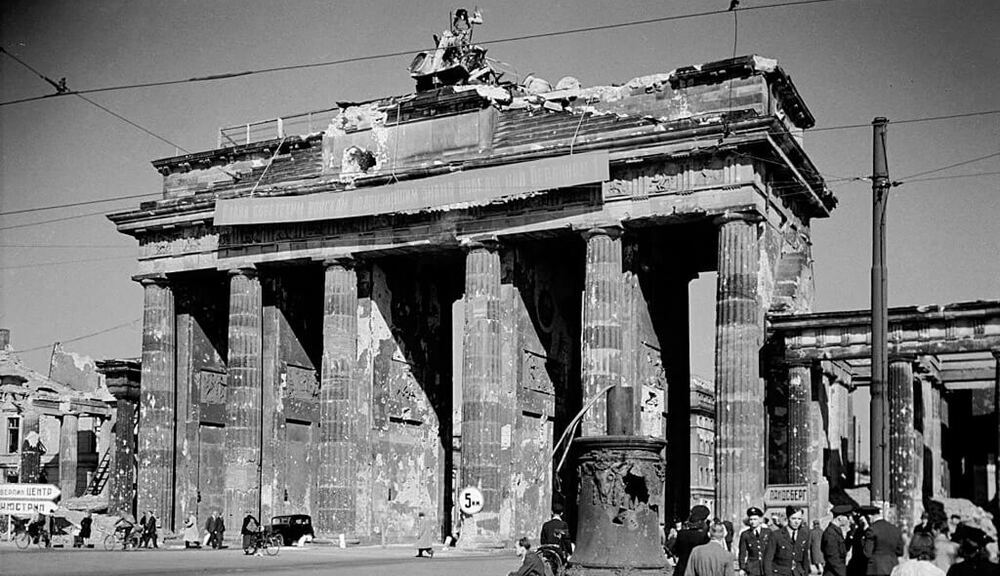

In 1945, the gates were badly damaged by bullets and shrapnel, and a projectile hit squarely in the quadriga. It was only rebuilt in 1958, until then a Soviet flag crowned the gates, which was later replaced by the flag of the GDR. During the Cold War, the gates were on the territory of the GDR, and after August 13, 1961, passage through them was blocked by the Berlin Wall.

The Brandenburg Gate can be found regularly in the city news. For example, in 2013, a drunk driver decided to do exactly what the gates were originally built for – drive through them. The result: a damaged pillar, third from the right, and a wrecked BMW. The unfortunate driver got away with a scare.

A century earlier, however, a more serious traffic accident occurred. Until the revolution, the central thoroughfare was reserved exclusively for members of the royal family and foreign ambassadors. But in 1918, insurgent soldiers took advantage of them and smashed through the gates with such speed that they buried the unfortunate Lorenz Adlon, founder of the famous hotel of the same name nearby. The entrepreneur survived the accident, but died three years later in the same place after another accident.

The Brandenburg Gate is one of the most common motifs for souvenirs, and with good reason. From classic prints on mugs and t-shirts to a chocolate miniature served in the Adlon Hotel’s restaurant, almost everyone in Berlin seems to capitalize on tourist interest in the Brandenburg Gate. Interestingly, the business surrounding the symbol of Berlin goes back 200 years. At that time, porcelain Easter eggs with gilded images of the famous landmark came onto the market.

As a key symbol of the city and an important monument, the Brandenburg Gate plays a crucial role in Berlin’s tourism industry. These historic gateways are recreated in a variety of forms and media, from photographs and postcards to souvenirs and gift items. The interest in the gates is so great that hardly any souvenir shop in Berlin can do without a replica or representation of the gates.

The gates are also popular in gastronomy. For example, a chocolate miniature of the landmark is served in the restaurant of the renowned Adlon Hotel – a delicious memory of the visit to the German capital.

This “tor business” is not new. Porcelain Easter eggs with a gilded image of the gates were sold as early as 200 years ago, underscoring the enduring popularity of this motif. This remarkable longevity is a testament to the deep cultural influence and historical significance of the Brandenburg Gate. They are not only a landmark of the city, but also a symbol of its eventful history and its position as an important hub in Europe.